Ramón Bonilla’s “Real State”

By Víctor D. Meléndez Torres, M.A., M.Ed.

KAMP — Ramón Bonilla

KAMP — Ramón Bonilla

It was fourteen years ago when I had my first serious discussion about art. My interlocutor, a formally trained artist, effectively challenged some of my previously held notions concerning the nature of art and its role in society.

The artist was Ramón Irwin Bonilla, and our initial exchange marked the beginning of a long conversation that continues to this day.

Bonilla is a Denver-based Puerto Rican artist who recently completed a two-year artist residency at RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver. He studied at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas in San Juan, Puerto Rico, alongside Guillermo Calzadilla of the world-renowned artist duo Allora & Calzadilla.

Life in Denver has had a very important impact on Bonilla’s work. In the spring of 2015, when he was painting the first pieces in his topographic-architectonic-geometric series, he shared with me his thoughts on what led to his incorporating “geometric elements” and “the architectonic aspect” in his oeuvre.

“I think it comes from working for a time with computer graphics,” he stated, in our native Spanish. “And all of that comes from living here [in Denver]: the mountains, but also the architecture here, which imitates the mountains—the lines and forms. But I’ve discovered a different appreciation regarding the spaces and elements that can be found through observation. I’m also using the concept of spatial memory to recreate these environments.”

More recently, he stated the following regarding his shift toward the topographic-architectonic-geometric: “More than working with architecture and topography, I’m considering concepts related to how space is perceived, categorized and modified or preserved.”

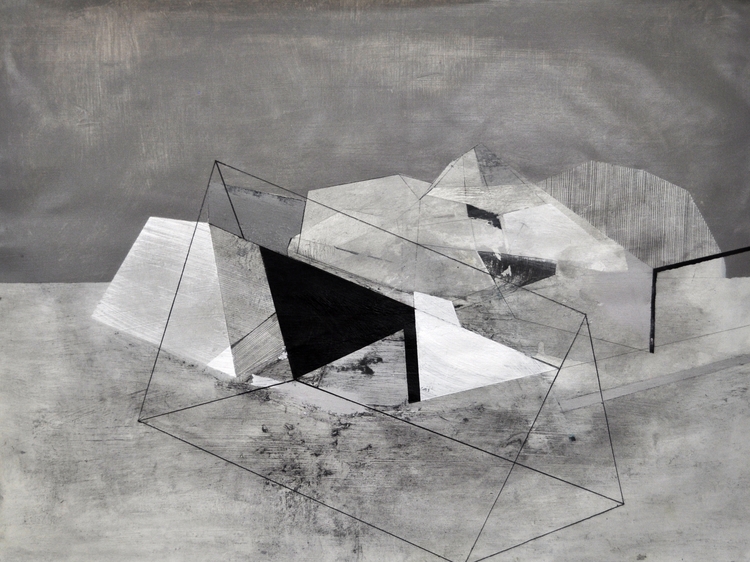

“Real State” (2015) is a representative example of this shift in Bonilla’s work. It’s an 18” x 24” acrylic-on-paper painting in which he used a limited palette consisting of white, black and a variety of gray tones.

According to Bonilla, “‘Real State’ alludes to ‘real estate,’ the concept of land as a possession that’s controlled or modified by its acquisition. This title also refers to the concept of ‘state’ as geo-political space. But this is an imagined or utopian state.”

In this piece, what appears to be an architectonic-geometric display of mountains and hills serves as backdrop to a large transparent triangular prism that prominently occupies the center of the piece. It’s that triangular prism which prompted me to delve into an exploration of the painting from a Lacanian psychoanalytic perspective.

Ever since Sigmund Freud’s “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood,” psychoanalytic theory has been a source of innovative aesthetic thinking. However, it is the work of the late French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan that has been of particular interest to many in the art world, including renowned art theorists Rosalind Krauss, Hal Foster and Mignon Nixon.

Within the rich and complex field of Lacanian psychoanalytic theory, there’s one notion that undeniably stands out: the Real.

The Real is that which eludes symbolization, that which is beyond the Symbolic (that is to say, beyond language) and cannot be put into words or images. In the words of Xavier University professor David Rodick, the Real is “the ‘excluded interior’ that has not yet been filtered into the realm of the symbolic order.”1

The Real can be thought of as the true nature of things—a kind of fullness, abundance or completeness from which we’re separated as a result of our entry into the world of language early in life. It’s the price we pay in exchange for becoming speaking subjects.

“It is the part of us which resists language; it either resists symbolisation or is non-symbolisable,” says London School of Economics sociologist Nicos Mouzelis.2 In the words of professor Marcos Engelken-Jorge of the University of the Basque Country, it “alludes to the non-symbolisable realm of the extra-linguistic reality that disrupts our meaning systems (i.e. the symbolic).”3

From a Lacanian perspective, contemporary art seeks to represent the Real. Ramón Bonilla’s work is no different in this respect. But his approach in attempting to traverse the unnamable and unattainable truth that lies beyond the confines of language is uncommon.

Bonilla’s use of architectonic-geometric forms in “Real State” captures the idea of our separation from the Real. The use of these forms allude to how the human mind produces a representation of an object in reality not as the object really is, but only as an approximation, as a kind of virtual image or map of the object—the mind constructs a map of the world, but the map is not the world itself. This map allows us to act in the world, but this doesn’t imply that we know the true nature of the objects in the world. They remain a mystery.

Of particular interest is the transparent triangular prism in “Real State,” whose visible emptiness evokes the idea that the true nature of objects in reality is outside of symbolization and remains a mystery, part of the Real.

Moreover, it’s hard not to see this transparent triangular prism as symbolizing the Lacanian concept of the constitutive lack. This lack is associated with the loss produced by our entry into the world of language early in our lives—a necessary loss that allows us to become beings-in-culture. What is lost with our entry into language is lost in the Real, the realm that is outside of symbolization. The fact that Bonilla’s triangular prism is large and occupies the center of the piece can be seen as suggestive of the constitutive, fundamental character of the lack, as well as the all-encompassing magnitude of the Real.

It is remarkable how Bonilla inadvertently produced a piece that entails what could be considered a representation of the loss associated with our entry into language, a loss that gives rise to our desire, that is to say, to our condition as perennially unsatisfied beings. Even though psychoanalysis is not among Bonilla’s concerns, the triangular prism at the center of “Real State” is singularly effective as a representation of the space of desire, the space of perennial dissatisfaction that is at the heart of the human condition, and its transparent quality can be seen as pointing to desire’s lack of a specific object (Lacanian psychoanalyst Bruce Fink put it best when he stated, “Desire is a product of language and cannot be satisfied with an object.”4).

Although the centrality of the triangular prism is evident, it isn’t the only aspect of “Real State” that alludes to our loss as beings-in-culture. The exclusion of hues—that is, a palette limited to white, black and gray tones—contradicts the idea of completeness associated with the Real. Like the triangular prism, it can be seen as symbolizing the lack that results from becoming a speaking subject.

The painting’s solid-colored surfaces are also worth noticing. They provide a sort of structural cohesiveness that’s not difficult to associate with language as something solid and stable. However, language is anything but solid and stable. As demonstrated by the Swiss linguist and semiotician, Ferdinand de Saussure, the relation between a word and a concept is arbitrary. And with Lacan, we learned that perfect communication is impossible (the subject “is always saying less or too much, in short: something other than what [she or] he wanted, intended to say.”5).

One could almost think that the structural cohesiveness gained from the use of solid-colored surfaces is an attempt to deny the arbitrariness of language. After all, to deny the arbitrariness of language is to deny the impossibility of grasping the Real, and in this sense, one might be tempted to consider “Real State” as representing the restlessness associated with an awareness of being disconnected from the ineffable, ungraspable truth, even though access to that truth would not be pleasurable in a conventional sense.

“Real State” is an interesting piece in many ways, but what makes it special is the structure that is projected into the triangular prism through the prism’s left end. It is unclear whether this structure is exclusively inside the prism, or at once inside and outside the prism. The structure’s left end seems to suggest that it is three-dimensional, but this is no longer clear as it progresses into the prism. It is also unclear whether its right end exits the prism and rests on the plane on which the prism itself seems to rest, or whether the entire structure is floating with approximately three-quarters of it doing so inside the prism. It’s even unclear whether the black part of the structure and the white part to its right are actually part of the structure itself or part of the plane on which the triangular prism seemingly rests.

It’s possible that the structure projected into the triangular prism is logically consistent, but it’s also possible to read it as a logical paradox. Insofar as this indeterminacy interrupts or disturbs the smooth reading of the piece, it could be considered an effect of “the real that goes by the name of object (a).”6

Object (a) is “the residue of symbolization,”7 an excess that “interrupts the smooth functioning of law and the automatic unfolding of the signifying chain.”8 It is in this sense “that element standing in for the Real within any symbolic system.”9

In “Real State,” the structure entering the triangular prism produces an effect that seems to be inconsistent with the rest of the painting in that the structure’s position is not clearly discernible. It is difficult to absorb into the picture, as there are many different ways in which it could interact with the other elements in the piece. The effect of this structure, therefore, could be seen as a residue, a kind of excess produced by the painting as signifying chain: the object (a).

A similar effect occurs in “KAMP” (2015), an 18” x 24” acrylic-on-paper painting in which Bonilla expanded his palette to include cerulean blue hue and light red. In this painting, at first sight, the light red square frame seems to be exclusively facing northeast. This is because there is a black line that seems to “touch” the left side of the square frame, forming an angle. The line is part of a seemingly transparent polyhedron in which the square frame seems to be contained. However, although at first sight the line suggests that the square frame is exclusively facing northeast, this is immediately thrown into question when considering that the line could actually be “resting” on the top side of the square frame. Then it is easy to see that the square frame could be facing northeast or southwest.

This indeterminacy makes “KAMP” similar to “Real State.” However, “KAMP” has something more. The polyhedron is, unquestionably, at once transparent and not transparent. Although the ground is visible through the polyhedron, the grey “mound” on the horizon is not, suggesting the presence of a logical paradox, a disruptive excess: an effect of the Real.

Bonilla describes his paintings as being “of the here, there and nowhere.”10 Perhaps the “nowhere” alludes to the “utopian state” to which he associates “Real State” (and to which “KAMP” also seems to be associated), one which we might call, “The State of the Real.”

Ramon Working

Ramon Working

‘Real State’ (2015)

‘Real State’ (2015)

Notes

1 David W. Rodick, “The problem of interiority in Freud and Lacan,” Journal of Arts and Humanities (JAH) 1, no. 3 (2012): 156.

2 Nicos Mouzelis, “Lacan and meditation: From the symbolic to the postsymbolic?,” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 19, no. 2 (2014): 128.

3 Marcos Engelken-Jorge, “The anti-immigrant discourse in Tenerife: Assessing the Lacanian theory of ideology,” Journal of Political Ideologies 15, no. 1 (2010): 74.

4 Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997: 178.

5 Slavoj Žižek, “The Lacanian Real: Television,” The Symptom, 9 (2008), http://www.lacan.com/symptom/the-lacanian.html.

6 Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995: 134.

7 Fink, Lacanian Subject, 83.

8 Fink, Lacanian Subject, 83.

9 Slavoj Žižek, Interrogating the Real. ed., trans. Rex Butler and Scott Stephens. London: Continuum, 2006: 372.

10 Ramón Bonilla, “Artist Statement,” accessed March 15, 2018, http://ramon-bonilla.com/about-avenue-1/.

Works Cited

Bonilla, Ramón. “Artist Statement,” accessed March 15, 2018, http://ramon-bonilla.com/about-avenue-1/.

Engelken-Jorge, Marcos. “The anti-immigrant discourse in Tenerife: Assessing the Lacanian theory of ideology,” Journal of Political Ideologies 15, no. 1 (2010), 69–88.

Fink, Bruce. A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

_____ The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Mouzelis, Nicos. “Lacan and meditation: From the symbolic to the postsymbolic?,” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 19, no. 2 (2014): 127–136.

Rodick, David W. “The problem of interiority in Freud and Lacan,” Journal of Arts and Humanities (JAH) 1, no. 3 (2012): 151–159.

Žižek, Slavoj. Interrogating the Real. Edited and translated by Rex Butler and Scott Stephens. London: Continuum, 2006.

_____ “The Lacanian Real: Television,” The Symptom, 9 (2008), http://www.lacan.com/symptom/the-lacanian.html.

Víctor D. Meléndez Torres, M.A., M.Ed. is a Puerto Rican organizational psychologist currently living in Santa Fe, New Mexico.